On Display

On Display

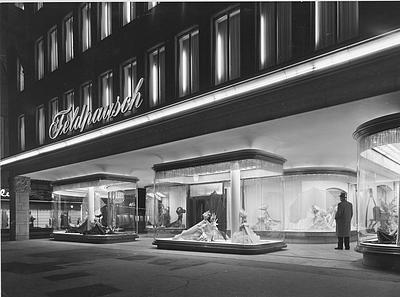

Apple store, after strip out, Bahnhofstrasse, Zurich, 2020. Photo Boris Gusic

"The Anthropocene marks severe discontinuities; what comes after will not be like what came before. I think our job is to make the Anthropocene as short/thin as possible and to cultivate with each other in every way imaginable epochs to come that can replenish refuge."

Donna Haraway

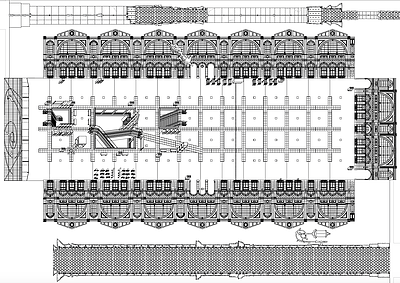

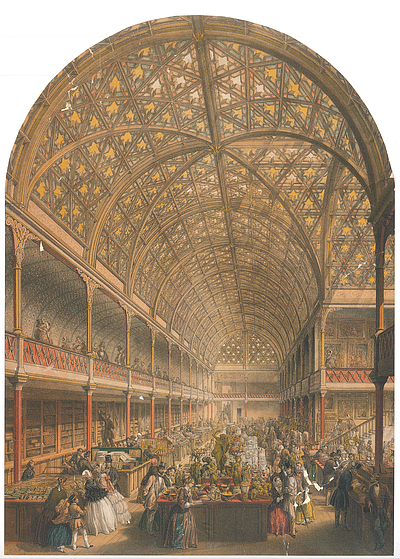

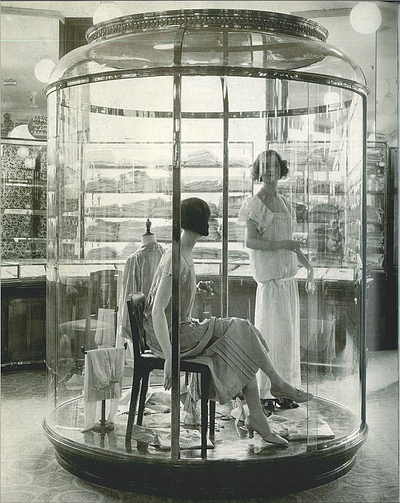

Shopping is over. Just like that. The social and economic revolution that gave form and style to the nineteenth century city has slipped into the palm of our hand leaving the city centre in search of renewed purpose. But if the human transactions are moving from over the counter to the digital ether, the desires, freedoms, walks and talks, will not be so easily privatised. The industrial revolution produced a previously unimaginable quantity and variety of things for which the department store was invented – following the prototype of the Crystal Palace (1851) a detournement of the gardener’s greenhouse - and produced an irresistible spectacle for the rising bourgeoisie. The architecture and in particular large glass shopfronts rivalled the marvels of museums and gardens. Behind glass, everything is seductive.

No doubt the dual reflection and transparency of expansive glass vitrines brought with it a new spatial experience, describing complex enclosures and openings, fusing all materials together to form the contemporary city. And perhaps it was glass itself that most changed the nature of public space. It promises openness through transparency but delivers exclusivity in reflection.

Far from being banal, mono-functional spaces away from the richness of metropolitan culture, the edge of cities are vital and multi-layered territories where work, leisure and sport are integrated in productive and ecological landscapes that have a great deal to offer contemporary life. The diversity of architectural types and landscapes documented in the Friesenberg Atlas could be seen as attempt to describe the nature of place. The design for Vereins made last semester have also demonstrated how small community organisations live together, interconnected with infrastructures, diverse topographies and ecologies to create a natural territory. And how even the smallest interventions can transform an ecosystem. Adjustments to walking patterns, to enclosures and openings on the surface change everything below or besides. Reimagining former architectures can create new things from the ends of others. It is a big space and a small space. Like the Eames’ The Powers of Ten, it is logarithmic, oscillating between the miniscule and the epic. Drawing the Atlas led the way with lines that literally describe the walk through the city, the blade of grass points to the lie of the land. Most of all, the Atlas and Verein have shown, far from being amorphous spaces, powerful spatial structures can bring beauty, biodiversity and human action into what can be seen as The Great Interior. This semester, we shall explore how larger structures bring another social, material and spatial disciplines to these edge spaces. We shall design an arena, a public building for performing and watching sport (and perhaps more). With origins as landscape structures in ancient times, arenas are typically defined by ground; dug in, cut and sculpted earth and stone. Then they rose out of the ground as pure-structure never fully enclosed. We will look for how structure and materiality can be the conceptual and technical engine of architectural design.

We shall frame the design process in terms of the complex and very much contested field of energy. What is embodied energy? It concerns the body of course, the athlete and the human physicality the arena celebrates. But it also concerns the urgent field weighing and measuring our resources as we attempt to recast our use of resources. It concerns design. The body may be analogous to our material world; fragile, weak, requiring extreme care to ensure its health, wellbeing and happiness. But also strong, inventive, resourceful and capable of extraordinary good just as it can inflict untold violences. How are these measured and calculated and what value does it have as our culture runs blindly towards catastrophic climate change? How do we design another great interior?

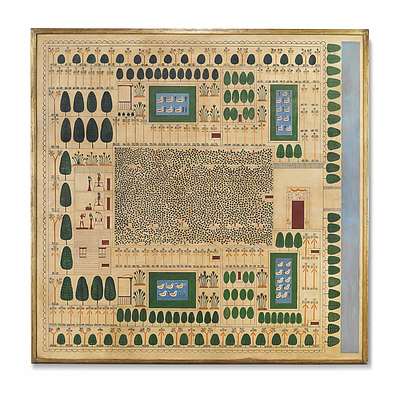

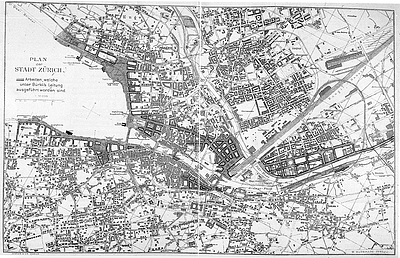

But Zürich’s main shopping street was not shaped only by the retail revolution. By the time the first iteration of Zürich’s Hauptbahnhof was built in 1847, the city walls had already been destroyed and the ditches sealed. Protest and disease are recurring themes in the city’s history. Textile workers’ revolts and the social divisions between town and countryside sparked the uprising in 1839 and the destruction of the old fortifications. Silk merchants converted their massive wealth and property into the banking institutions of today’s city, their houses and gardens forming the footprint for metropolitan expansion. Following cholera epidemics of the 19th C, the muddy ditch, the Fröschengraben was sealed over to become the Bahnhofstrasse, and with it the last traces of an agrarian society. Commerce, protest and later civic action led by Bürkli transformed a town on the river into a city on the lake.

The gardens and streams of the 18th century disappeared under stone and concrete as the city reached deeper into the block filling it with loading bays to supply our shops and equipment to keep them cool. The excesses of spaces and things that caused irreversible climate change have finally provoked a reaction in society and most urgently in architecture.

We will continue to work in our garden in parallel with our architectural journey. Working together, we will begin the next chapter of the garden. We will establish a new series of rooms in the landscape in parallel with those of the studio and of the city. And, weather permitting, use the rooms in the garden as a studio space. After a semester of interior confinement, we will use our spaces to maximise our time together and our time outside, in the garden and in the city. Or is the city already a garden waiting to be rediscovered?

You will be designing two rooms, one interior and one exterior and, most importantly, the membrane that holds them together or separates them. Like Split or the spatial transformations imagined in romantic ruins, the city will change again. Can a new natural city emerge from the interaction of two rooms? Can glass still provide the magic encounter? These two rooms will start with the architecture and nature of the city of today and project them with all the force of current events into the future. The city will be different. Architecture will be different. Materials will be different. Nature is different. But they are rooted in where we came from, be it a muddy ditch below the street or a distant land.

The new rooms will be found in the existing city. They may be turned inside out, reversed, excavated or filled but all forms of re-use because as Bruno Latour has famously stated, design is only ever re-design. The end of retail could precipitate a radical transformation of the city, recasting what exists in a new natural order sensitive to the needs of humans and every other species with whom we share the planet but have expelled in our drive to consume.